The young girl, the cinema, the revolver, the night

January 1, 1987 – November 12, 2016

Mélanie:

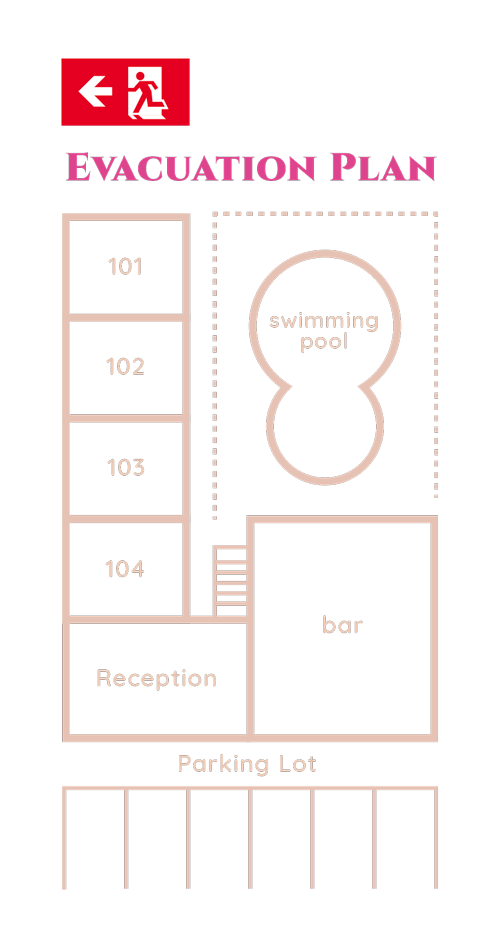

It is half past midnight and the Bar is still full of customers. The music takes hold of everything. Everything is fluid and slow in Angela Parkins’ arms. I lack time to understand. There is no more time. Time has entered us in a minute detail like a scalpel, time compels us to reality. Time has slipped between our legs. Every muscle, every nerve, every cell is as music in our bodies, absolutely. Then Angela Parkins’ body moves slowly. Her whole body is pulled downward. Her body is heavy in my arms. My arms are heavy with the body of Angela Parkins. There is no more music. Angela Parkins’ sweat against my temple. Sweat on my hands. Angela, silence is harsh. Angela! A tiny pattern on the temple, a tiny little hole, eyespot. Angela, we’re dancing, yes? Angela Parkins has no more hips, no more shoulders or neck. She is dissolving. Angela’s eyes, quick the eyes! There is no more balance between us. My whole body is faced with disaster. Not a sound. The commotion all around like in a silent movie. At the far end of the room, there is longman’s impassive stare. The desert is big. Angela Parkins is lying, there, exposed to all eyes. Angela is dissolving in the black and white of reality. What happened ?

[…]

Of course Mélanie is night teen.

Simon, April 13, 2016

As you know, Mélanie the teenager has been with me for a long time. That being said, I realize that, generally speaking, the image of the young girl has fascinated me for a while now and this interest extends beyond the scope of Mauve Desert. There’s nothing original about it. Many men before me have been interested in her. There’s Little Lili or even The Little Thief by Claude Miller. And then there’s Manon of the Spring by that other Claude, Claude Berri. In these films, gazes lack nuance. Multiple perspectives (mainly masculine) converge on the young girl. Looks charged with desire, but also, for some older characters, with nostalgia or resignation. Of course, Miller and Berri are of another generation, a time when a girl became a woman in a man’s arms. It seems to me, however, that this image transcends masculine desire. It overtakes it and, in doing so, it becomes an object of fascination in what becomes an artistic quest for those filmmakers. That being said, it also seems to me that in those films, the young girl is more of a plot device than an actual character. Through her, various male characters discover themselves or even break against her. Even if the young girl has an effect on them, they are the true subjects.

In your writing, desire is present too, and is one of its driving forces. Not only in Mauve Desert, but in most of your work. This inclination is what brought you to Mélanie, but unlike Miller and Berri, your relationship with her is twofold; desire and self-identification merge, and Mélanie gains depth. The stakes change and incarnations of desire (also seen in Little Lili) shift completely. It may be a question of perspective, but it’s more likely a question of positioning. In your writing, the image of the young girl takes on new proportions. She is the protagonist of her own story and the concerns of the text are her concerns. It’s about her desire and her point of view on her reality.

Nicole, April 26, 2016

The young girl. There’s only one young girl in Mauve Desert. It’s not Mélanie, but her cousin Grazie, whom Mélanie would very much like to sleep with. At this point we could obviously lose ourselves in conjecture or have a long discussion about the masculine-feminine that’s in all of us or promoted by society in the form of passive/active roles and behaviours. Every “young girl” is given this label because of the male gaze alone. She is the object of desire and a thousand other imaginary systems that at times rejuvenate and at times make one reflect on his or her life. You understand this very well. Why do you say “young girl” when words like “teenager” or “girl” exist, words that are ambiguous, but dynamic, like a group of girls? Mélanie is Mélanie, at best a teenager who, as you put it, “is the protagonist of her own story and the concerns of the text are her concerns.” She could also be a teenager in the sense that James Dean was a teenager.

A young girl (whether in bloom or not) has already been categorized as heterosexual. I’m thinking of Nabokov’s Lolita and other books (See Va et nous venge by France Théoret. I need to do my research.) …

Simon, April 10, 2018

I emphasized the Bomb because in the American-style portrait of Mélanie in my imagination, the teen had until recently obscured the landscape behind her.

Or maybe it was out of focus.

And now I learn that the explosion of light I had assumed was dawn is actually an atomic flash.

It was Jean-François Chassay who revealed this backdrop – which I had only half perceived – to me in his preface to the new edition of Mauve Desert. He speaks of an imaginary apocalyptic world and notes that the novel provides clues that link Mélanie’s story to a historical backdrop, that of the development of nuclear weapons in the American desert. A theme woven beneath the surface that I didn’t immediately notice the first few times I read the novel. I did feel the vibrations in the form of anguish emanating from Longman and even contaminating Mélanie’s existential quest. All the same, when you notice these references to History, there is no doubt about it: Longman is Oppenheimer’s poetic double and Angela Parkins is thrown from her horse by the explosion from a nuclear test.

You answer my question by explaining the way that the patriarchy developed and spread through time and segments of society. However, I get the impression that this “apocalyptic imaginary world” that pervades the plot is twofold and operates under the surface.

On one hand, as I was saying, it positions an entire network of symbols, forces and male imagination on the periphery of Mélanie’s cosmogony, encircling this small fictional universe built around a motel lost in the desert. In addition, Longman is interwoven with this universe and operates from the inside. This creates a twist in the narrative, and necessarily puts the characters’ feminine point of view into perspective. It’s this twist, I think, that allows Mauve Motel to avoid becoming a kind of feminist Disneyland. Although it is to some extent a story of hope, Mauve Desert is still imbued with a dark lucidity, as evidenced by its ending.

On the other hand, this imaginary world sets the stage for addressing the theme of death. Teen fiction writers, you told me, deal with the themes of transgression, sexuality, intensity. Here, Eros goes hand in hand with Thanatos, as he often does. As she discovers desire, Mélanie is already becoming familiar with death. A violent death, Angela’s death, that she will not see coming and that will come from the periphery where Longman looks on impassively.

It moves in a circle. Concentric circles. It might be the spiral you describe in Surfaces of Sense.

This method of placing the “guys” on the outside gives Longman a central and distinct position in this world of women. This must be another qualitative difference between guy and man that lends weight – again, a poetic weight – to your “demiurge of destruction.”

Have I told you that when I first read the novel, I associated the explosion – somewhat unconsciously – with the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995? It’s those images that came to mind. The nuclear threat, at least until very recently, wasn’t such an important part of my life for it to surface spontaneously when evoked poetically. Has this blunder altered my reading of Mauve Desert? I don’t think so. The clues and the keys scattered throughout the texts are only signs of its richness. There is therefore a reading level – that is neither inferior nor superior – in which a phrase such as “The exact calculation of languages that have ended up in space like an explosion” is more of a poem than a clue. And I’m pleased that with each reading, the text continues to reveal itself to me in a way that is both personal and collective.

That’s literature, isn’t it ?

Simon, April 13, 2016

I’m looking at the image of the young girl from a heterosexual (“straight”) perspective and adding a few words. Why? Why is she fascinating? Maybe it’s because the young girl’s time (or the adolescent’s time) is one where possibility overwhelms determinism. The euphoria induced by an unlimited, uninterrupted horizon is charged with youthful energy that is almost as boundless. But there’s more. For a long time, the image of the young girl has also been paradoxically fragile. The young girl possesses strength she must develop precisely because of her vulnerability. The young man is more fragile, less self-assured. More awkward too. The young girl knows she is being observed and she knows she bears the age-old (and unjust) burden of violent desire and fertility.

In Mélanie’s universe, which is fiction, desire is directed toward raw, organic, sensitive, living material

or toward objects so simple they never stop working.

The revolver.

The revolver is always loaded.

Simon, March 29, 2018

In Mauve Desert, I was particularly struck by two masculine “entities.” There is Longman, of course, but also those “guys who came from far away” who are mentioned briefly. Only one of which is armed. These masculine presences hover like a threat – a past or potential one – a bit like the nuclear threat during the Cold War.

In one of our first exchanges, we both discuss the varying perception a person can have of a particular time depending on whether that person has lived through it, whether it’s a matter of memory or knowledge. And yet, since I was very young when the Berlin Wall fell, the only memory I have of the Cold War comes down to a few afternoon’s worth of films dubbed into French on TV. Any understanding I have of the backdrop of Mauve Desert stems from my knowledge of history and is completely divorced from my personal experience. I would love it if you could tell me how the social context led (or did not lead) to the emergence of Longman (alias Oppenheimer) in the pages of Mauve Desert.

And where do those guys who came from far away come from?

Are you drawing a link – tenuous or circumstantial though it may be – between the emergence of feminism and the evolution of the Cold War or the nuclear arms race?

How and why does fear appear in Mauve Desert, and what is the relationship between fear, Longman and the television?

And speaking of Longman, what does he represent? What is his relationship to the collective imagination (to collective fear)? And what about propaganda ?…

Nicole, April 2-6, 2018

Dear Simon,

You refer to two male figures, Longman and those “guys who came from far away” who appear early in the novel. I use the word “guys” to emphasize their anonymity. Longman bridges Antiquity, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, communism, socialism and neoliberalism. The guys come from far away from the little story, but enjoy the privilege of being “guys.”

Simon, April 4, 2018

Guys “who came from far away,” of which only one was armed and all the others blond. A poetic strangeness that relegates the masculine world to the “outside” and brings a somewhat spooky sheen to “the inside” of fiction. It feels unreal because it’s different from the reality that we know, which is – to put it bluntly – patriarchal. The great thing about this excerpt is that the poetry allows all of it – this microcosm in which power relationships between men and women are partially reversed (even though Longman will not accept it) – to go undetected, without the reader noticing it at first. Well, by “reader,” I mean me.

Nicole, April 2-6, 2018

“Only one of them was armed.” I admit that I was playing here with the idea of singular vs. plural: “All the others were blond.” I was thinking of the “blond” youth from the last war who (of course) have blue eyes in the translation, which make them “superior.” The words may be poetic, but my allusion isn’t. It points to sexism through the metaphor of racism.

Longman represents the history of patriarchy, which – regardless of whether it was codified by religion or law – is a history of violence, domination, exploitation and alienation.

You may be right to ponder the unexpected semantic shift between the real Cold War and the one between men and women, although there is no comparison between the methods of deterrence used. In terms of gender, war – a destructive force (death, rape, slavery) – the Cold War – a force of negotiation and endurance – and peacetime (marriage and reproduction) go together. I find it interesting that for women, religion and the law have been responsible for killing them, treating them as inferior, subjugating them and justifying “charges” against them and “sentences” imposed upon them. But it’s clear that as feminist strategies evolve with the arrival of new reproductive technologies, social media and “new” gender identities, the strategies of the current Cold War are also evolving according to the potential of new technology. For example, the dirty bomb (also known as a radiological bomb or radiological dispersal device) is an unconventional bomb surrounded my radioactive material designed to explode and disperse when it is detonated. Its only purpose is to contaminate the area surrounding the explosion, a bit like how fake news contaminates the credibility of a political candidate or politician’s party. Women have had to bear the brunt of patriarchal dirty bombs and fake news for a long time, and it has taken us a long time to understand that. In both kinds of Cold War, 21st century-style, survival and reproduction are – in theory – made possible by technology.

Simon, April 7, 2018

I’m tempted to say, of course, like everyone who witnesses Angela Parkins’ murder and who is there in the bar as she falls to the ground in slow motion, that I didn’t see anything. Not the battle of the sexes and not even the Cold War motif, the first few times I read the novel.

Very young, I had no future like the shack on the corner which one day was set on fire by some guys who ‘came from far away,’ said my mother who had served them drinks. Only one of them was armed, she had sworn to me. Only one among them. All the others were blond. My mother always talked about men as if they had seen the day in a book. She would say no more and go back to her television set.

Right before this passage, there is the idea of reality being swallowed up by the indescribable desert. And there is the “I” that refers to being “very young” and speeding across the landscape. The mother is evoked right away through the car, the Meteor borrowed without permission.

Right after this passage, we follow this “I” who is “wild with arrogance” and who, at fifteen years of age, “driv[es] into the night with … absolutely delirious spaces edging the gaze.”

This “I” is of course Mélanie, which we will soon learn.

The burned shack and the guys who came from far away passed through the corner of my eyes and imprinted themselves onto my retinas. They stayed there like an afterglow, while I, like Mélanie (who prefers to live fast), was already moving on to other things. Between the desert and the teen’s thirst, the shack, the guys and the mother’s comment still had time to set the scene, better than the landscape would have done. The desert is not a backdrop here, but a living, “vibratory” entity, as you would say. The centre of this fictional universe is the mother. The reception, pool, clients and even the desert revolve around her. This is Mélanie’s world. And the novel depicts the energy Mélanie exerts to extricate herself from this gravity.

“Very young, I had no future.” From these first words, Mélanie is gathering momentum, heedless of the obstacles in her way. With a future to reinvent and reality giving way under her feet, Mélanie steps hard on the gas pedal to bend the light, as she says. Over her shoulder, we get a brief look at the mother in front of the television set, before once again being swept away along the mauve and orange lines that shape the landscape. We will barely have time to catch a glimpse of the fire in the night, the moonlight on the butt of the revolver and the glints of light in the blond hair of the guys gathered there. The poetic strangeness of a clashing scene that has no place in this orbital system, but is still present, like a narrative off-camera shot. In a way, the guys are relegated to the periphery of the narrative, to an exterior from which we can better situate this seemingly realist fictional universe, but in which certain power relationships are reversed.

You ask me what I understood from “only one of them was armed” and “all the others were blond.” The question caught me off guard because I’d never stopped to think about it, to be completely honest. The image just stayed with me. The shack in flames reminds me of another one that falls from the sky and smashes against a small Idaho country road in the Gus Van Sant film. Does my memory deceive me, or wasn’t River Phoenix blond as well? It’s a poetic strangeness that I like and that must have guided me through Mélanie’s cosmogony, without my being aware of it. This familiar, if somewhat outlandish, microcosm in which all the stars are women apart from Longman. And apart from those “guys,” of course, like a speck over the horizon.

Very young, there was no future and the world resembled a burned-out house like the one at the corner of the street torched by ‘strangers,’ so said my mother who had served them a drink. My mother thought only one of them was armed but no concern came over her for all the others had blue eyes. My mother often said that men were free to act as in books. She would finish her sentence then, once the uneasiness had passed, sit in front of the television set.

The paths of fear often lead to fear of the other, and then to insularity. As I reread these excerpts in order to better respond to your question, I realized that it was the words of the “original” version that I’d remembered. I think that with this version in mind, I simply overlooked this passage, superimposing my first impression onto it. I’d noticed that the translator exaggerates desire in her version, that the eroticism is more apparent in her hands. Now, I realize that all the sensations/emotions are magnified in that version.

That includes fear, which overrides the poetry in this excerpt.

The fear of a mother who is a catalyst, in a way, giving Mélanie the push she needs to leave.

A double-edged fear.

When I read it again, the thing that struck me was the association between the words “strangers,” “armed” and “blue eyes.” It’s no longer distance that’s being evoked, but difference. The kind of difference we’re suspicious of. Everything that is unfamiliar to us, our habits and our world. The mother is reassured by the eye colour of most of the “guys” in the group, but is worried about the one whose eyes are different. That one is armed. And the house will be torched.

The thing that drew my attention here is the circulation of meaning between versions. I told you that in my mind, the original and translated version blend together, so that my interpretation and the translator’s interpretation end up merging. And the poetry swells until it overwhelms the words with which it is created, colouring the entire fictional construction, Mélanie’s universe.

Nicole, April 8, 2018

In this paragraph, the mother is trying to teach her daughter about men. Her reasoning for doing so is unclear, since she doesn’t want to condemn all men. However, she uses the phrases “only one of them was armed” and “all the others had blue eyes.” Her confusion is reflected in the phrase “My mother always talked about men as if they had seen the day in a book.” There is a double constraint between “the greatness of Man” (science, philosophy, art) and the reality of the guys (everyday life). The mother is not at all reassured by “blue eyes,” but here the author feigns innocence in order to mask the discomfort with poetic metaphor. Then the mother returns to the television set, believing that she is escaping from a reality ruled by violence and fear. To a certain extent, she does the same thing we do with all the screens that distract, stimulate, enchant, lie and alienate us.

By the way, I should add that in my mind, “the shack on the corner which one day was set on fire” was set on fire by the KKK. I use the word “shack” because it was poor people who lived there and who were the victims of the fire, whose heinousness we try to forget by temporally distancing ourselves from it with the expression “one day.”

In short, the author is angry and Mélanie steps on the gas pedal.

I asked because I wanted to know what you took from these phrases and to see how meaning shifts in the vastness and encounters between words. All this to say that we’ll never be done exploring meaning and the pleasure of knowing that it is so unclear, so open, like the widespread idea that we need to stay alive.