A TALE OF REFERENCES

(mostly those of Simon Dumas)

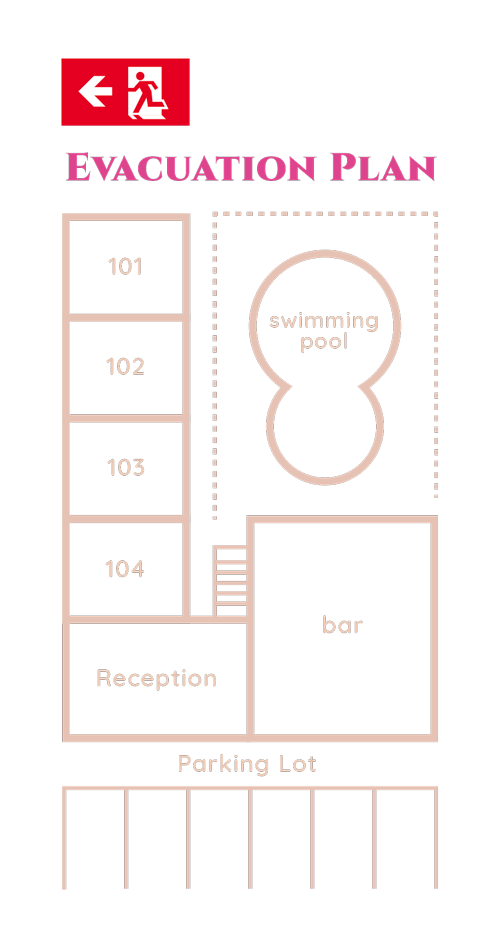

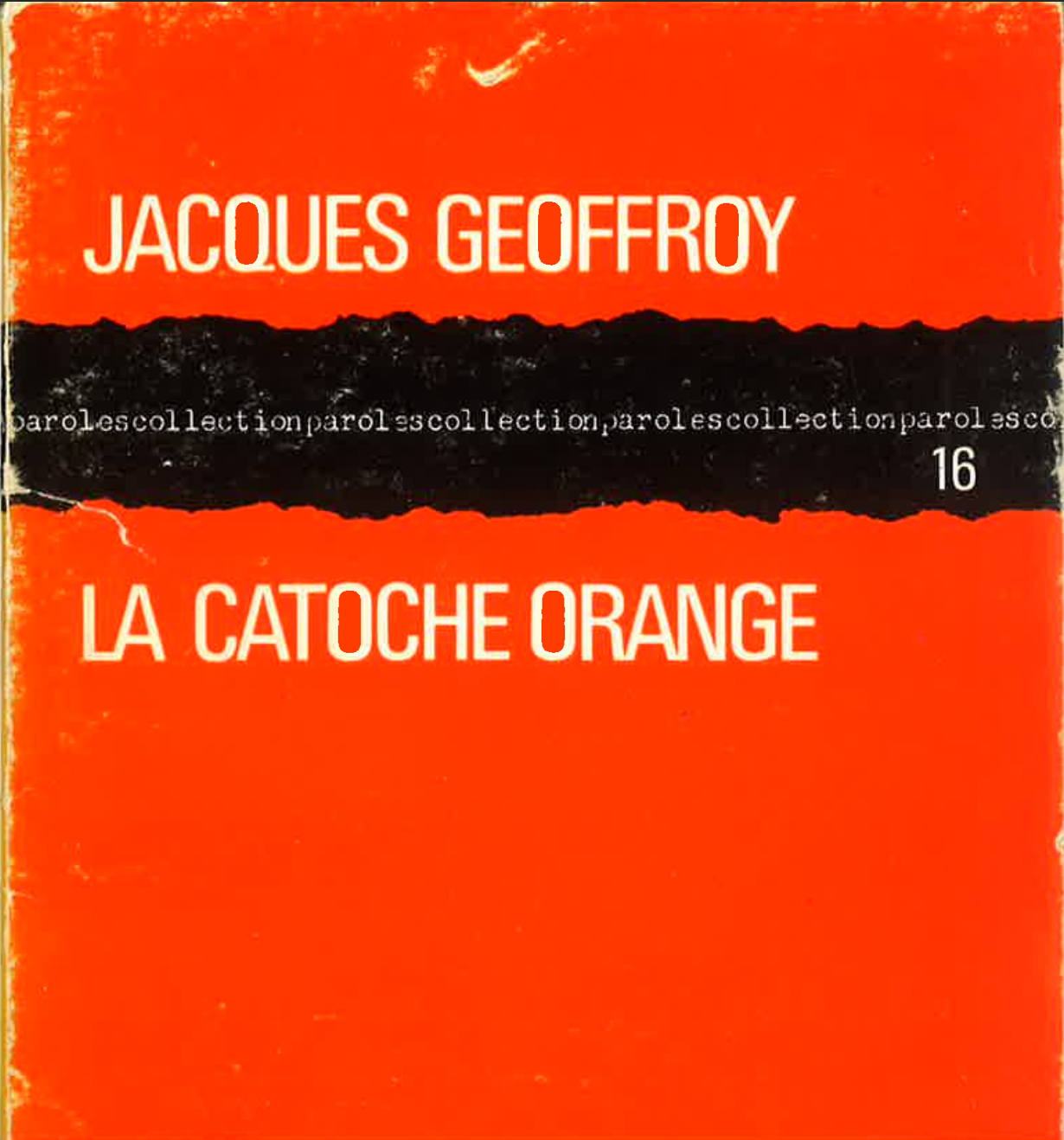

Claire Côté, a humanities professor at CEGEP Lévis-Lauzon, introduced me to Jacques Geoffroy’s only book. That was my first contact with the Mercury Meteor.

19 years later, I became the owner of a 1963 Mercury Meteor made in Ontario. I resold it after the film shoot, which took place in Québec City in August of 2017.

Three years earlier, I’d written two poems inspired by my research on the American version of the car.

Spiritual successor of the Medalist, nineteen fifty-six adopted sister of the Monterey Mercury Meteor, first generation

nineteen sixty-one big car. Two or four doors. Two or three speeds, a fourth (overdrive) available. From two to six tail lights, three on each side on the high-end model. Meteor 600 Meteor 800 Top of the line Monterey (formerly entry level) Slant six cylinder, one barrel, a hundred and thirty-five horsepower Various displacements of eight cylinders, in a V configuration The most powerful with a capacity of three hundred and ninety cubic inches three hundred and thirty horsepower two hundred and fifty kilowatts.

Second generation, nineteen sixty-two and sixty-three: assembled in Dearborn, Michigan and Kansas City, Missouri

Loses a size, goes from large to medium format. Ford Fairlane shared its body with the Meteor in nineteen sixty-two, a larger version of the Ford Falcon’s Two or four doors Two or four speeds, automatic or manual Six or eight cylinders that range in capacity from a hundred and seventy to two hundred and sixty cubic inches.

Nineteen sixty-four and sixty-five, Mercury doesn’t offer a medium-sized model, the Ford Comet fills that niche. Nineteen sixty-six, the Comet name changes hands from Ford to Mercury.

By all accounts the same car.

These poems, written in Mexico City, appeared in a book published in 2013 bearing the name of the main character in Désert mauve, Mélanie.

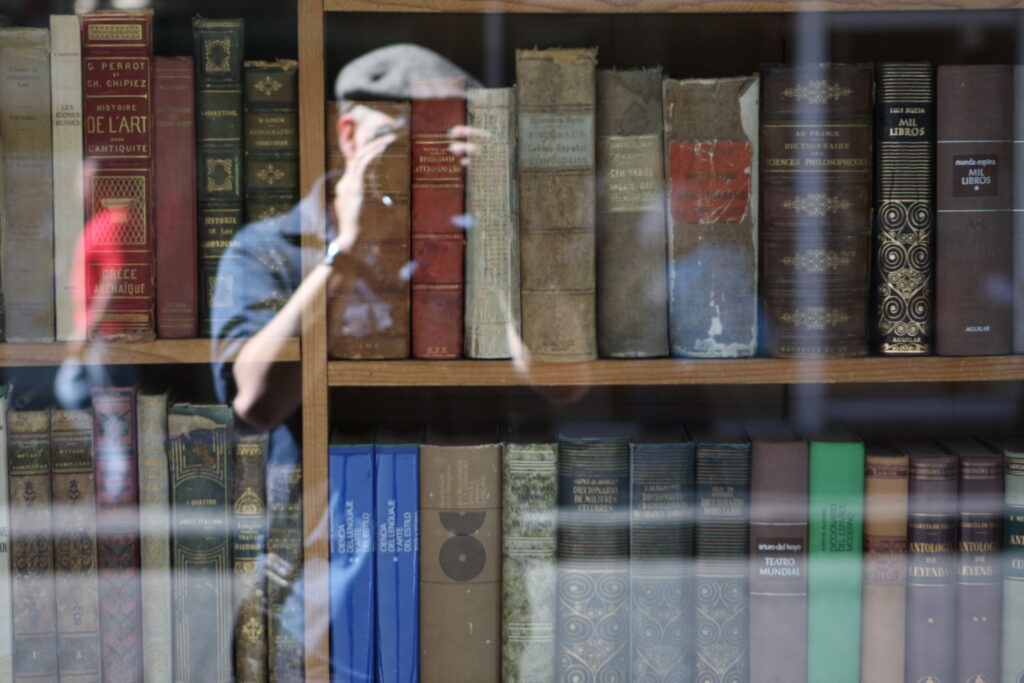

In Mexico City, where I was in residence, I found seven copies of El desierto malva, the Mexican version of Brossard’s novel.

In Mexico City, where I was in residence, I found seven copies of El desierto malva, the Mexican version of Brossard’s novel.

At the time, my writing process drew heavily on an Argentine film I’d seen in a theatre down there.

My father was the lone reader of a blog I kept during my stay.

I had assembled a group of women and asked them to read the novel and try a few writing exercises. Lyliana Chavez and Mariela Oliva were game.

It was there, too, where I researched the Mercury Meteor. I learned that the car is ingrained in the imagination of a generation, but only in Canada.

I am too young to have lived through the golden age of car design the 1960s turned out to be. Instead, my family had a Ford Tempo (the Mercury Topaz’ twin) whose lines were markedly less inspiring. But it’s the wind’s fault she’s so ugly.

That line “ready to pounce” is practically lifted from a poem by Carl Lacharité in his series Le vivant. It’s a text I’ve heard many, many times as it was used in a collection of shows and performance staged by Rhizome in various locations between 2009 and 2018.

By frost and by salt the fern lies with its obscure geometry, driving its roots into the intimate secret of the dead. Their power stirs in it: it’s the birth of water, scattered, always renewed. It demands a birth, another place and all that’s visible, fold after fold. It demands lines, shapes, that could make a line, a shape drawn up before pouncing. What to do with all this neglect, so close to the body, commanding the landscape?

//

Who said spending hours on YouTube was a waste of time. I saw Fellini at work on there. Impressive set, inspirational person.

A Felliniesque wedding, you said.

And we danced to the music of Philippe Katerine.

//

I attempted, very awkwardly, to tackle the subject of the male gaze in film. Here’s an example which I find both wordy and poetic.

You also talked about Va et nous venge by France Théoret whose writings draw a diagonal in the sky of the 20th century.

//

On July 5, 2016 — with Marco Dubé, Geneviève Allard, Marc Doucet — we talked. About literature, about love, about childhood, about adolescence and about Désert mauve.

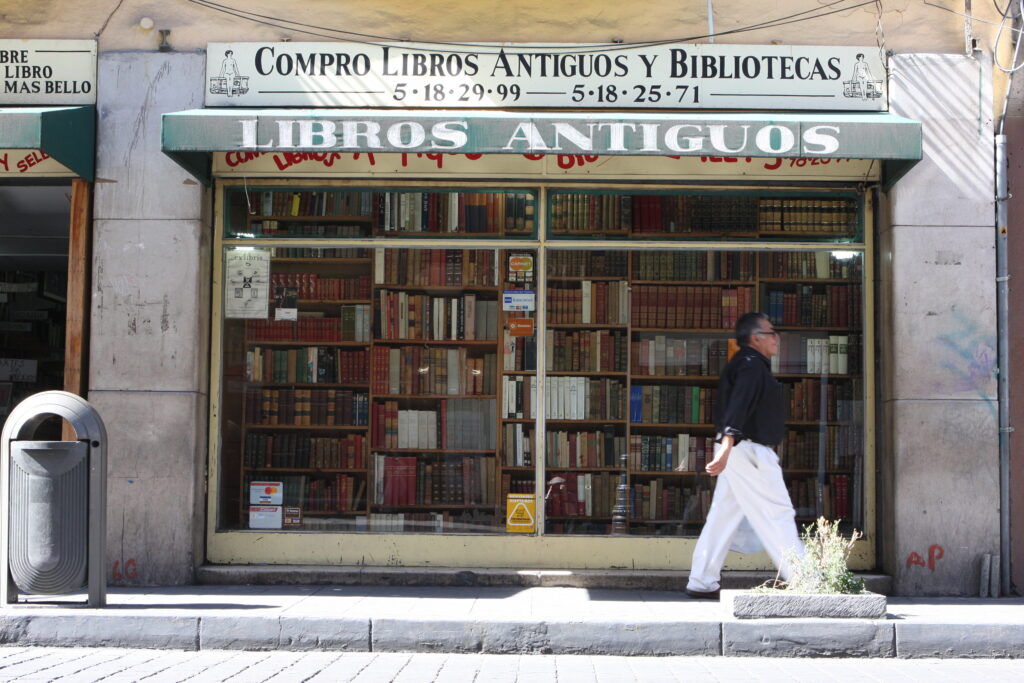

In 2013, I received a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts to write a screenplay based on Désert mauve. In the proposal I submitted the character of the translator, Maude Laures, finds Laure Anstelle’s book in a Montreal used bookstore and decides to translate it. Early on, I realized I wasn’t interested in faithfully following the narrative of Brossard’s novel. My intention was not to adapt the novel for the screen, but to transpose the processes it describes. Translation processes, which in my screenplay, become intertextual and interdisciplinary creative processes. I ended up with a screenplay for a film-performance, a kind of user guide for a film crew travelling the route between Québec and Tucson. Along the way they talk, preparing themselves for the worksite that is making a film. A film that could just as well be called We are Maude Laures. An upcoming film that is still in search of someone to make it.

In the end we didn’t make a feature film, but a show that called on the codes of literary talks, theatre and film. We still needed characters though. On the subject of casting the teenager who would play (more like embody) Mélanie and the real risk of not finding the one, you said “the wrong face or wrong body could compromise the film.” I couldn’t help but think of Duras’ disappointment, verging on rage, when Jean-Jacques Annaud’s adaptation of L’amant came out. A disappointment that led to her rewriting the story, this time adding footnotes in case “this book is made into a film” :

… the child can’t just have a pretty face. That could jeopardize the film. There’s something else at work in this child — something “hard to get around,” an untamed curiosity, a lack of breeding, a lack, yes, of reticence. Some Junior Miss France would bring the whole film down. Worse: it would make it disappear. Beauty doesn’t act. It doesn’t look. It is looked at.

From a footnote in The North China Lover by Marguerite Duras.

We talked a lot about casting – anticipating that face, hoping for the right contours, the right expression, dynamics and energy. Jean-Jacques Annaud auditioned 7000 young girls. We clearly didn’t have the same means, but we were very, very lucky.

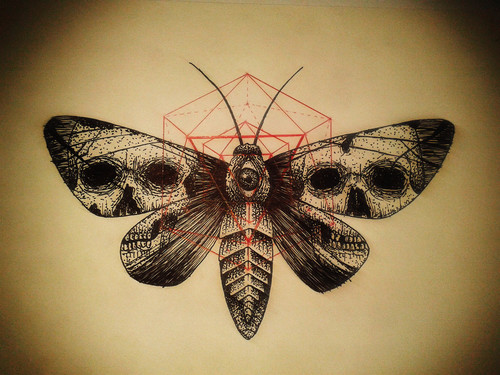

Then there was Mélanie’s tattoo. I didn’t like the idea of a fake tattoo. I told you as much. Instead of making people believe that a decal was a real tattoo, I wanted to show that one of us (on team Maude Laures), not necessarily the person who played Mélanie, had actually gotten a tattoo of the big sphinx. I thought it should be you. I told you, I argued, you refused. My request was of course unreasonable, but the discussion that came out of it was very interesting.

Then we started filming.

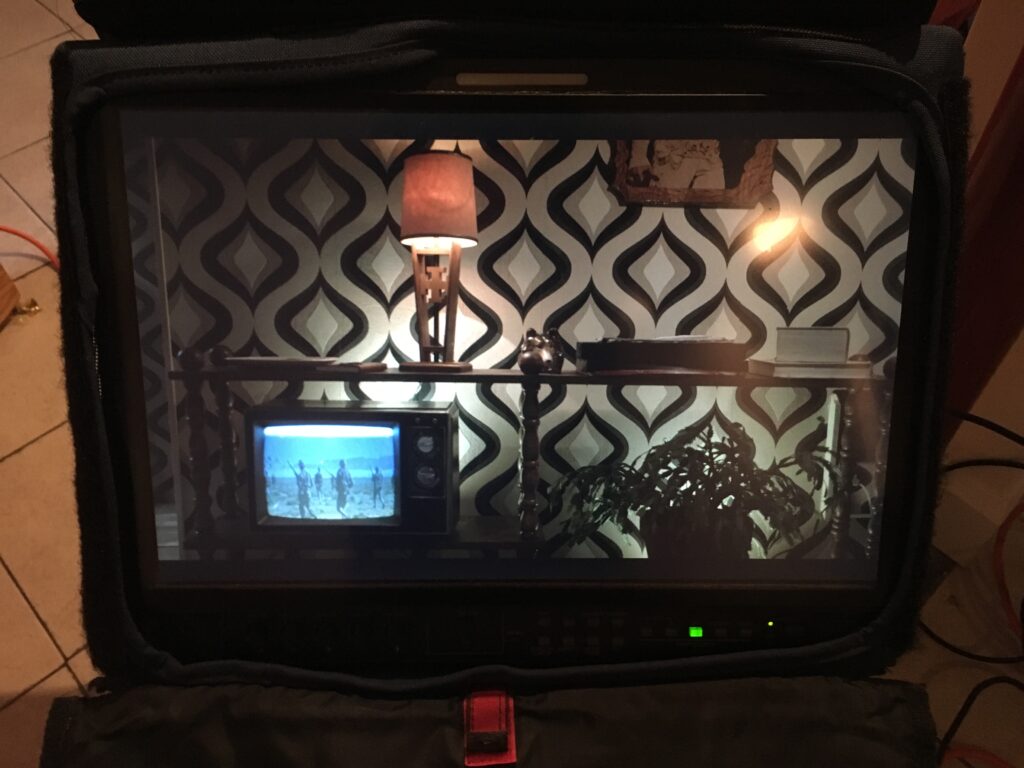

Not a feature film, but a few cinematic scenes to use in the show we were planning. The second day of filming was dedicated to the television scene.

To feed images to the TV set, we chose archival footage on YouTube of soldiers in the Arizona desert walking towards a mushroom-shaped dust cloud. A random video, which we had not chosen, autoplayed afterwards.

//

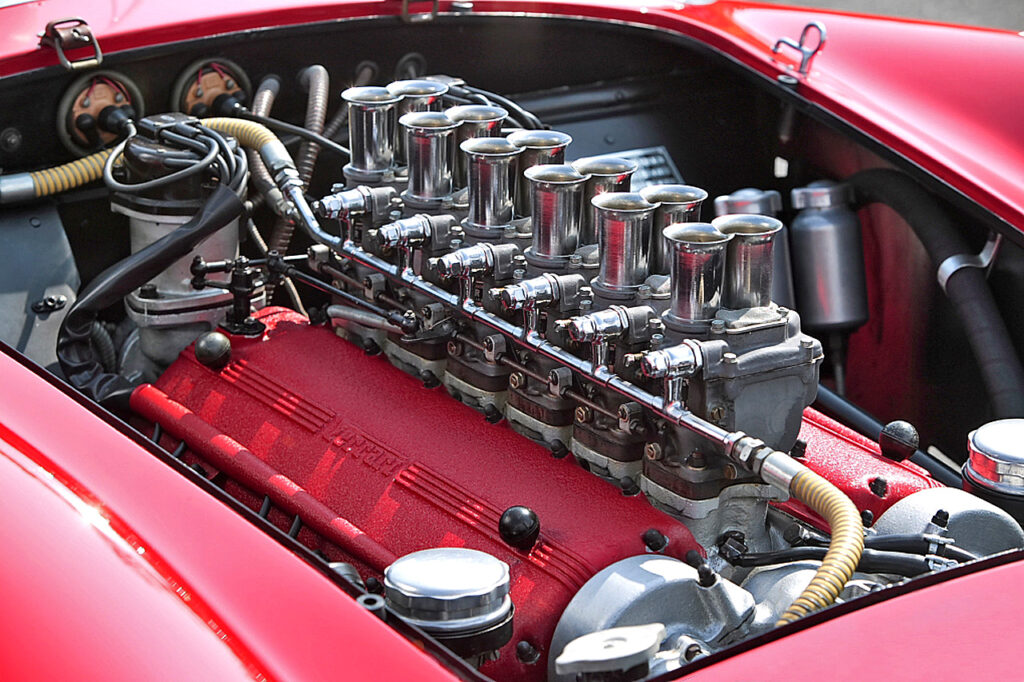

I was in Brussels working on another project when my mind made the connection between the motor and the atomic explosion.

Truthfully my imagination was already full of these expanding atoms, whose force is on an unimaginable, obscene scale.

The contrast is striking with this poem by J. Robert Oppenheimer, which is as calm and cold as a stone at night :

It was evening when we come to the river

with a low moon over the desert

that we have lost in the mountains, forgotten,

what with the cold and the sweating

and the ranges barring the sky.

And when we found it again,

in the dry hills down by the river,

half withered, we had hot winds against us.

There were two palms by the landing;

the yuccas were flowering; there was

a light on the far shore, and tamarisks.

We waited a long time, in silence.

Then we heard the oars creaking

and afterwards, I remember,

the boatman called to us.

We did not look back at the mountains.

The very same man who proclaimed that the visual effect of the bomb would be tremendous.

//

LLast May 21, you were writing me in an e-mail that your last message could be: “I’m at Brasserie Outremont waiting for Hugo Amaral, the Portuguese translator of Désert mauve. And I’m reading an article by Caroline Ferrer called Traduction, fission et trahison. L’hologramme de J. Robert Oppenheimer dans Le désert mauve de Nicole Brossard. »