Beauty, The Night, Screen, Body, Tattoos

January 1, 1987 – June 7, 2016

Mélanie:

Some day perhaps, I will tell my life story. Some day when I am no longer fifteen with a heart whose spirit has a sense of wonder. It’s saying it all when I talk about the night and the desert for in doing so I am stepping through the immediate legend of my life on the horizon. I have abused the stars and screens of life, I have opened up roads of sand, I have quenched my thirst and my instinct like so many words in view of the magical horizon, alone, manoeuvring insanely so as to respond to the energy traversing me like a necessity, an avalanche of being. I was fifteen and I knew how to designate people and objects. I knew that a hint of threat meant only kilometers more to go in the night. I pressed on the accelerator and clash, swear, fear, oh how fragile the body when it’s so hot, so dark, so pale, immense silence.

Nicole, April 27, 2016

Your relationship with Mélanie has probably been in continual transformation for nearly fifteen years (in images, books, and projects). As for me, my relationship with Mélanie began while I was writing the book. Mélanie is an intersection, a meeting point where the adolescent space (a significant one for all human beings) unfolds, touching all aspects of who we are: intellectual, sexual, emotional, spiritual, identity-forming (who am I?), existential (what is living, life?). This is what gives her rebel wings, her vital self.

Simon, April 25, 2017

The accident of a landscape

like a familiar face

yesterday however

barely landed

yesterday we didn’t know

a face pierces the landscape

that we didn’t know before

yesterday again

and suddenly death exists

Nicole, May 5, 2016

Sometimes the soul is so tranquil it stills in the afternoon. In the woods, there’s nothing captivating. It’s May now, but it’s like a dull March. I won’t even mention the trees.

We love things when they exist for us.

There are also some unforgiving objects.

Is the matter you speak of an image?

It’s because the light recurs without necessarily being the same that you seek it so intensely and would like it to be your own. The objects it reveals, live or through a screen, are worth their weight in mystery, pleasure, anguish and questions.

Nicole, April 27, 2016

Images. I am a visual person, but I don’t have a good sense of images. I would say that for me, images are always replaced by an aura of ambiguity and uncertainty, a haze that makes a person think of beauty, fiction. The beauty always springs from an association with a stroke of fiction (like a “stroke of genius”) the ingenious improbability of chance or art.

Being there, not being there. Representation, images, photos, films, holograms, traces, the image in the mind, the thrilling image, the haunting image. The image-enigma that takes you beyond reality: the virtual.

In our next exchange, we must talk about the “theatre of matter.”

Simon, May 4, 2016

Casting and Desire

Language is another form of representation. Unlike theatre and cinema, colour or stone. In our relationship with language, there is a distance that is also virtual. Not because words are disembodied, but because they are an incarnation of the invisible matter of the body.

An invisible intimacy.

You talk about characters as the fulfillment of a desire. Could you say it’s a concentration? All the elements of the character are there, waiting inside of you, but also in your words, scattered or hazy, until a desire allows you to see if for the first time.

You talk about characters as screens onto which we project ourselves. But this screen could also be a meeting place, where the projection of the author meets that of the reader, since readers must project themselves onto the text.

That being said, there are two screens. One is in the text and the other is in front of our eyes. The character’s body is not the actor’s. The latter is singular, unique and bound as much to their unique physical traits as they are to their personality. The character is necessarily multi-faceted, the result of a negotiation between the author’s projection and the reader’s interpretation.

The actor’s body is necessarily a screen. It is a screen in the sense that it is interposed between the viewer and the object. The actor’s appearance is not negotiable. Or not much: makeup, costume, hair …

Writing a film, as I have for Mauve Desert, is above all a matter of visualization. Much more so than with a novel (whereas you could say that poetry is part images, part music). Sort of a “practical” visualization. Unless, like The Decline of the American Empire, it consists of 176 pages of dialogue with a few stage directions here and there to let you know whether the scene takes place in the kitchen or the garden. In places where there was no dialogue, I had to “show” things without doing the director’s job, meaning without giving camera directions.

20. INSIDE/DAY. MAUVE MOTEL

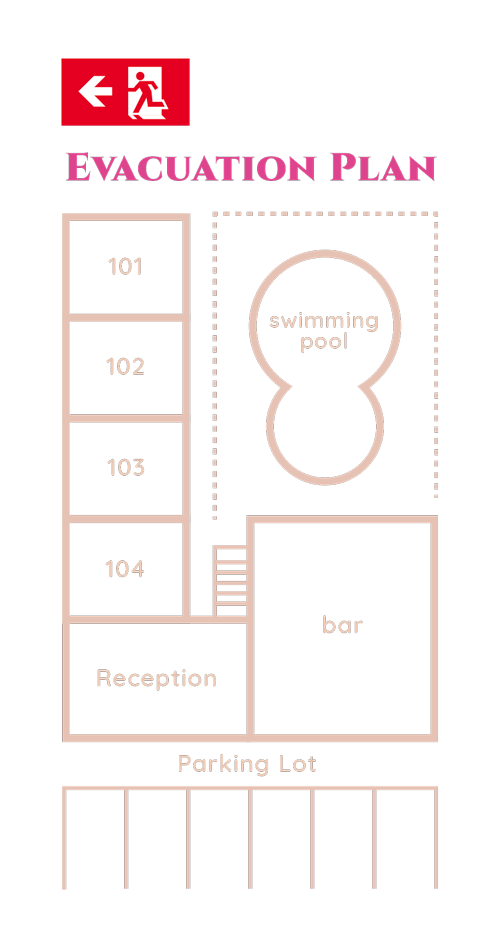

The door opens suddenly. Mélanie strides past the reception desk. She throws the car keys to her mother at the reception desk. Her mother wants to say something, but doesn’t have time. Mélanie has already reached the hallway.

Laminated posters on the walls: a large Saguaro cactus in the snow, a thunderstorm in the desert.

We follow Mélanie. She walks down the hallway. Shoulder, neck, hand, motel key. She reaches the door to her room, opens it and goes inside. She disappears and a cleaning woman can be seen vacuuming at the end of the hallway. Beyond that a closet, cleaning products.

The ice machine.

The loud vending machines.

The carpet.

The lights.

The pay phone.

The emergency exit at the end of the hallway.

Visualization.

Projection.

Does Mélanie have short hair? I’d never thought about it. It’s dark – I know that for sure. Also sure that Grazie is blonde, but maybe the right actress could make me change my mind, compromise.

During our discussions on desire in film and creating a show, you talked about “casting” several times (I know Guy Bertrand disapproves of me using the English word). I imagine it’s important because the body of the actress we’ve chosen, her facial expressions, her movements, will be a screen between Mélanie and the way you imagine her, the way I imagine her (certainly, they are two different images).

This might be what I mean when I talk about “theatre of matter.” The conflict between the meaning we want to give things (by organizing them using language or other systems of meaning, such as film) and what those things – landscapes, inventions, civilizations – tell us about themselves.

How do you imagine Mélanie now, nearly thirty years after the book was published? What are your expectations of the casting (the process and the result)? Is it really an image of Mélanie or a desire more related to film ?

Nicole, May 14, 2016

I may not have expressed myself well when I talked about characters, but I am still convinced that the characters in the novel are the result of a projection of life in one form of another (the self, the appreciated self, the hated self, or the appreciated/hated alter ego). There is a system of cultural and idiosyncratic values we can imagine as tectonic plates sliding against each other, overlapping, etc.

The word “negotiation” is perfect. This explains why I say that I write novels every five years: to negotiate with reality.

The actor’s body and face: everything you’ve said makes sense to me.

It’s important, essential, when I watch a movie. Although, I admit that it wasn’t such an important factor when I watched The Turin Horse or Sacrifice. The script and the movie are so intelligent or aesthetic that you throw yourself into the view of life that’s offered to you.

So you can imagine how vital the Mélanie actress is. The wrong face, the wrong physique could ruin the movie in a way. It makes you wonder about the serious or simple humanity that resides in a face. For women, it’s very complicated. They’re encouraged to affect weakness or vulnerability from very early on. Apparently it’s reassuring. An interesting prototype is the flight attendant who must always be charming, reassuring and authoritative all at once. Her “role” guarantees her neutrality. Excuse the digression.

Mélanie’s hair is short. Grazie’s, light brown.

Nicole, May 15, 2016

How I imagine Mélanie, thirty years later.

Tough question. I must have been about forty when I started writing my first drafts of Mauve Desert. Mélanie: poetry, freedom, love of movement, of travel, of the horizon, sunset + the mythical tools of civilization (car, revolver, TV).

Mélanie is a concentration of vitality, of intelligence, of rebellion, of desire, of solitude, of challenge. She’s comfortable in her athletic body; her movements are quick and precise. Her plans are never explained because she lives in the present, the beauty of the moment. She wants to discover. What strikes me is that Mélanie likes to be alone. As though she were an essence rather than a person (a rebellious fifteen-year-old girl living in the Arizona desert, rebelling against the world that surrounds her – stupidity, greed, violence – a girl consumed by the cruel beauty of the desert).

Mélanie is not studious, since where she lives, nature and daily life are more important than becoming a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer, an architect. There’s nothing feminine in her future except the love of another woman. Living with two mothers, she’s a misfit.

Is it really an image of Mélanie or a desire more related to film?

Casting. I have to like Mélanie’s face.

She can be athletic: a young rebel who likes to move.

She can be calm: she learns by observing. At the bar, for example.

She learns by listening.

Nicole, March 30-31, 2016

Tattoos: I’ve always liked tattoos. I’ve never gotten a tattoo. To me, tattoos are a symbol of rebellion and pain and are also undoubtedly a rite of passage. Tattoos are fashionable now and, since everyone gets them, they’ve lost some of their meaning. I’m still convinced that getting many tattoos, and often is a way to displace pain, to make it forever visible to oneself or to others, to bring it from the inside to the surface – in short, to never forget its presence in the skin, to remember it and to be proud of it.

Tattoos still have meaning, but they don’t fascinate me anymore as symbols of rebellion and delinquency. That being said, there are some girls’ tattoos that I won’t soon forget. Actually, they’re probably also related to sexuality. As for how, that’s more complex.

Simon, May 25, 2016

Tattoos/Representation

Would you get a tattoo? Is there something you would have wanted, but never got? You talk about marking the body and, strangely, it makes me think of representation. Permanent drawings not on, but in the skin, an individual desire engraved on the natural body, in its collective or familial sense. My mother was profoundly hurt when, at seventeen, I had a black panther tattooed on my thigh. I was not rebelling, not pushed by a desire to re-appropriate my body. I just nonchalantly fell victim to peer influence (the word “pressure” would be too strong). The panther doesn’t have meaning for me and never has. I had chosen a popular design from a cheap catalogue (what’s called “tattoo flash”): I just wanted to cover the unfinished drawing by an amateur tattoo artist I’d met at a party one night. Now all I’ve retained from the event – other than a pretty faded drawing on my skin – is my mother’s reaction. I had vandalized something sacred she had given me, altered (without giving it a second thought) the fruit of her gestation and labour. In writing this (actually, I’m transcribing the pages of the notebook I filled last night, but now I’m really getting away from my subject), I realize the body’s collective quality. The individual’s body doesn’t just come from a mother; it’s descended from a line and already part of the social body. It may be because the latter is breaking down, and the individual has more value than all other components of society, that tattoos are now generally accepted. This, regrettably, robs the act of being tattooed of its rebellious aspect. Each body finds itself at a point of tension between strict aesthetic canonicity and the desire to be unique. Everyone wants to be unique while being the same. Painful standardization in a world that glorifies the image of the rebel. In this context, the body really is like a screen – a white rectangle with standard dimensions – and tattoos become a means of distinguishing oneself from others, imprinting oneself with one’s own desire.

The body-screen/representation.

A screen: we project something onto it. Before the lights go out and the projector is turned on, it’s nothing but a white surface, it looks insignificant. What illuminates the human body, then? What fire, what desire? We’re called consumers, taxpayers, shareholders … the word “citizen” is used less and less often. Some would like us to believe that we are not part of a social body, but simply a mass whose individual desires can be restrained and then redirected toward consumables, toward the production of wealth. But not our own, of course.

Did this lead to our parents’ rebellion?

You mentioned James Dean.

And Mélanie’s?

And her mother’s?

Why does Mélanie get a tattoo?

Why is Angela fascinated by this tattoo?

And how did you come to construct this fantasy? With what materials?

As we’ve been working on transposing the reality contained in the fiction of Mélanie onto another creative dimension – space and time restricted by representation – the idea of leaving a trace of the process as concrete as ink on skin has been developing. Actually, it was you who suggested emphasizing the image of the tattoo, but through which medium? The natural medium for tattoos is skin. At first I was thinking of the actress who would play Mélanie. Would she be willing to get a tattoo? She would have to be completely dedicated to the project. I discussed idea with some of the people around me. Invariably, they tell me that a temporary tattoo would suffice, bringing us back to “pretending” and therefore to representation. I’m becoming more and more attached to this notion of commitment (to the audience, but also to the project, the other people involved), to the idea that one of us – you, me, or someone from the team – will be marked by the project. Physically. I’m more comfortable (is that the word?) with an attitude (commitment) that will allow us to say (even quietly, to ourselves) that we did it “for real.” Of course we know that regardless of whether the tattoo is temporary or permanent, the effect of the performance is the same. It changes nothing. The thing that changes is our relationship with the audience, the unspoken pact we’ve made with them.

And our relationship with the project.

It’s even more significant since we are not the actors, but the creators of both the text being performed and of the actual performance. Allow me to demonstrate my point using an anecdote. From the time I helped with the line-up for a festival in Québec City. We’d brought in a production entitled Kolik by the French director Hubert Colas. An actor (the amazing Thierry Raynaud) delivers a text by the German writer Raynald Goetz for one hour. Seated at a transparent table covered with 144 glasses of vodka, he spills out a flood of lines while killing himself with alcohol. The stage direction is sober, precise and powerful. The actor drinks and speaks, speaks and drinks the 144 glasses that are actually full of water. During the performance in Québec (it was also performed in Montréal), Laurence Brunelle-Côté, a self-proclaimed “undisciplinary artist,” was in the room. At the end of the performance, the person sitting next to her thought it necessary to correct her error. He explained to her that it wasn’t vodka, but water; not the author, but an actor. Disappointed, she exclaimed, “Oh … it’s a play!”

Laurence’s reaction isn’t completely absurd. In Québec City, the event was part of the Poetry Month line-up where most events consisted of authors reading their own text in front of the audience, often taking great risks, making them more like performances. When this story reached my ears, my first thought was that if the 144 glasses had been full of vodka, the actor would be dead. Still, the reflection on Laurence’s reaction – a very sincere and spontaneous one – has stayed with me. Even more so now that I am asking you to get on stage with me, to perform, both as subjects and performers (really?).

Angela Parkins – the surveyor who makes Mélanie understand the meaning of the word “desire” – is also a screen in a sense. Mélanie projects a future onto her that might never exist. Total freedom, emancipation, an affront to convention, flying in the face of ubiquitous, oppressive fear. Sometimes I confuse Angela/Mélanie, Mélanie/Angela. That’s why I thought the drawing of the sphinx, the moth whose patterned wings look like a human skull, was on Angela’s shoulder. But I’m talking about characters – they’re your characters and, as such, are they not a reflection of your desires? Your quest? Your projections?

Would you get Mélanie’s tattoo? Would you be willing to make this tattoo the first manifestation of fiction in the very real performance space ?

Nicole, June 7, 2016

“an individual desire engraved on the natural body”

“the body’s collective quality”

“It may be that because the latter is breaking down […] that tattoos are now generally accepted.”

I’ll try to answer two of your questions:

Why is Angela fascinated by Mélanie’s tattoo?

First of all, I should tell you that you’re correct: Mélanie is the one who has the tattoo. On page 87, when Angela Parkins answers “Nothing” (it’s in italics in the text) and changes the subject, it’s because she’s uneasy seeing death, a representation of death, on such a young girl. Does she see her own death? I think that’s what I was hinting at.

It’s the desert where death is undeniably on the prowl. Danger is everywhere and inevitably fear, excess, and escapism (speed, alcohol), loneliness, vulnerability; the desert should demand humility, a kind of wisdom in those who inhabit it. Angela Parkins is all these things at once.

Tattoos have always fascinated me. And obviously, I found the death’s-head sphinx moth particularly interesting, aesthetically and symbolically. Having a hybrid of beauty and death, natural flesh and a skull, on her shoulder. Basically, a powerful symbol in the skin. That species is on the poster for the American movie The Silence of the Lambs. It’s also pervasive in Jussi Adler-Olsen’s The Marco Effect, published in 2015.

The death’s-head sphinx moth, Acherontia atropos: it has distinctive markings reminiscent of a skull that resemble a mask.

The Hells Angels also use the skull as their symbol. It was a sign of total delinquency and liberty even before the H. A. became criminals. I’m thinking of the 1953 movie The Wild One and its motorcycle gang, when the motorcyclist became the rebel’s icon.

How did you come to construct this fantasy of the tattoo? With what materials?

Tattoos are a part of me.

The skull is part of my cinematographic image of the rebel because of The Wild One. You see it on the leather jackets and on the bikers’ rings.

The sphinx moth was an accidental find from a dictionary search. Even then I made a mistake, since I called it the “great sphinx.” There’s another sphinx moth, the sphinx elpenor, that’s pink, very “pretty.”

144 glasses of vodka.

I don’t know what pact you make with the spectator. As for me, I offer them thoughts, sensations, emotions that spring from the way we shape our words.

What we call fiction – as opposed to reality – is simply what is true, plausible and, because it is thwarted for all kinds of reasons (censorship, marginality, abnormality, daily-mundane work), is dreamed, imagined, fantasized about and conceived outside of what is materially or culturally obvious. And added to this is colour, each person’s tone: enthusiasm, depression, pain, injury, a scientific, rebellious or tidy mind, etc.

Fortunately neither murders, nor actual rape, nor 144 glasses of vodka are permitted in the theatre. Long ago, they talked about ritual, sacrifice, the thirst of God. Now, we talk about social networks, rape and assault in real time. What counts more: the idea, or the dramatization of the idea? Okay, some have been saying they can “hurt themselves without mutilating themselves” – Orlan, body art (tattoos, piercings, scarification, etc.) – since the sixties. Art doesn’t say no to violence, blood or excess.

There’s also the idea that you can do it once, or many times.

To me, art is more of an insightful, formal montage, a testimony to a possible reality that has not yet occurred or been understood. For example, Proust discovered psychological laws, Stendhal too. Unknowingly, these painters projected real images of cells, synapses, and aerial views onto their scenes before their time. Musicians have also undoubtedly produced sound sequences that resemble what we could hear in the cosmos, under the sea, or in our own bodies.

I want to be a subject and a performer in words. My body will do its best to perform sincerely.

If necessary, it could be uncontrolled for five minutes, but that’s assuming that the words aren’t controlled either.

In all of my novels, I’ve detected a pattern: my characters are projections of yes and no. They are variations of 1) what looks a lot like me, 2) what looks a little like me, 3) what I desire, 4) the complete opposite of me, or 5) what is quite simply an element of necessary presence. It’s the same with so-called supporting roles, passers-by, extras.